I understand why some people don’t like baseball. For the most part, it’s a boring game. Most of your time at a baseball game is spent waiting for something interesting to happen. Most pitches don’t result in solid contact, and most contact results in an out. Watch baseball long enough and you understand. The game makes sense, and several minutes of nothing happening suddenly becomes exciting. In fact, it’s even better when one team makes nothing happen for the entire game. A perfect game. One of the most thrilling things to happen in the entire sport of baseball is for 27 consecutive batters to fail to make anything thrilling occur.

This film is actually about the New York Yankees repeatedly failing, making it the greatest film of all time.

In a way, baseball teaches us to expect disappointment. It makes us cynical, and lulls us into a sense of false security that the game will continue to disappoint. The crack of the bat is nothing but a loud strike, fouled down the line. The soaring fly ball will stay in the stadium. No amount of effort can push the runner to first base before the ball beats him on the throw. And then, once our expectations are ground into dust, baseball surprises us. It gives us the moment we stopped hoping for. All the excitement is condensed into a series of quick bursts. Suddenly there are runners on base. The pitcher is sweating. And now that hit–that unlikely hit–could actually put the run on the board.

This is why I’m writing about a baseball game again, less than two months into this project. Because while some people don’t like baseball, I love it. That doesn’t explain, however, why I’m writing about another NES baseball game developed in Japan and released in the late 80s.

“Yes, I have a question for the man in the blue suit. Why do you need six microphones for three people?”

Baseball Stars came out over a year after RBI Baseball, in 1989. These two games, along with Bases Loaded, comprised the three major baseball games for the NES. I promise I won’t write about Bases Loaded, though the third installment does suddenly reinvent the game of baseball as a grueling saṃsāra, in which the player must play game after game until achieving the developer’s idea of perfection by following Ryne Sandberg’s Eightfold Path.

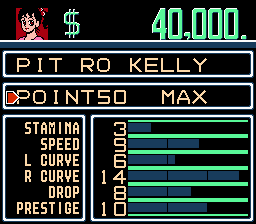

The real reason I am writing about Baseball Stars has little to do with my love of baseball. Any sport could have been the one to implement the two features that really stood out in Baseball Stars. The first is a bare-bones GM mode, allowing players to create their own teams, organize their own league’s, hire, fire, and trade players. This is was critical to the success of Baseball Stars , since it didn’t feature MLB or MLBPA licenses. This level of customization was unprecedented in console gaming at the time and paved the way for similar features: roster editing, franchise modes, and the bizarre abomination that was NFL Head Coach.

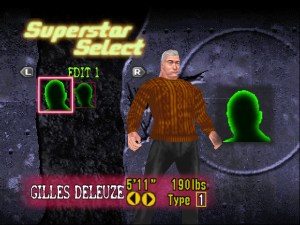

It’s a good thing he wrote down his cunning strategy of “make winning plays!” because he might have forgotten otherwise.

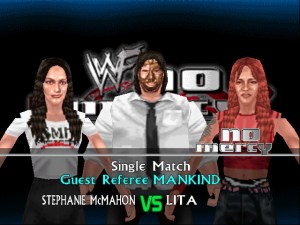

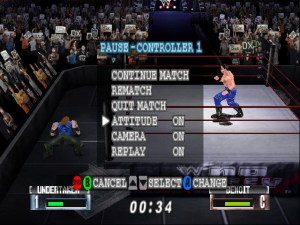

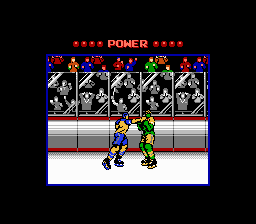

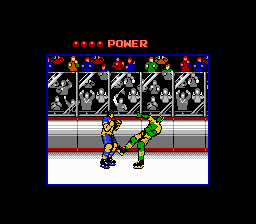

The second unique feature about Baseball Stars hasn’t become so ubiquitous. Unlike any mainstream team sports game of its time, and unlike almost every single one to come after, Baseball Stars allowed female characters. More specifically, the default set of teams featured an all-womens squad (the Lovely Ladies, which is an unfortunate name but it was 1989), created players could be women, and with a cheat code you could make an overpowered female team.

Representation of women in gaming has been a hot topic recently, as the world is beginning to wake up and realize that the demographics have changed. For years, playing video games was perceived as “for boys”. It’s important to note that this isn’t just a sexist assumption, based in the dumb gender roles that have seen boys scolded for playing with dolls and girls steered away from the t-ball squad, but also fixated on youth. Video games were for kids, specifically male kids and no matter what Midway wanted everyone to believe, even so-called mature games like Mortal Kombat were marketed in that direction.

Video games, and specifically the phrase “rated M for Mature” have been singlehandedly responsible for the semantic drift of the word “mature”.

As consumers grow up, gaming is trying to grow up. Everyone involved is realizing that the market is–and always has been–much larger than just boys. People are starting to understand how the industry has been pandering to a very specific demographic for a long time, and how that pandering is excluding other groups. And the very boys who have spent the last twenty years being pandered to in video games are FURIOUS if anyone suggests this should change.

Progress is slow. Call of Duty: Ghosts will be the first in the series to allow players to use a female avatar in multiplayer, but it took until 2013 for a series with a billion entries to finally make this addition. Assassin’s Creed only featured a woman in the lead role in a Vita spinoff, Assassin’s Creed: Liberation. Grand Theft Auto V, probably the biggest game of the year, has three main characters and they are all, for some reason, men. Granted, there are indications that you will be able to choose a female character in the online component, but Rockstar is so so secretive about everything that there is no telling what the options will be and you’ll probably have to pick which former U.S. President to play as in an homage to Point Break.

Baseball Stars was an extreme outlier, to the point where sequels to Baseball Stars removed the ability to make women’s teams and female players. Granted, it was a cosmetic change and the implementation of it was rather weak–the brief animated cutaways and even the fielding didn’t feature female player models–but removing it was still a shitty thing to do.

Female players looked identical to male players in the field, which is to say that they looked like chubby men in skin tight jumpsuits.

At least in sports games, the inclusion of female characters has been dire since the first Baseball Stars. Tennis games and the occasional golf game have featured women, but the major U.S. team sports have been devoid of the option. Arguably, the reason is because women don’t play these sports in the leagues that are being portrayed within the game. There are no female MLB, NFL, or NBA players. Baseball Stars proved in 1989 that this is not a good excuse. Understandably, developers will not stick women on a roster where there aren’t any female players. However, there’s no reason to disallow created players to be female. And don’t say it’s player models. Most modern create-a-player modes allow for a wide variety of height, weight, and body shape.

The absurdity of this was made evident when EA decided (much to their credit) to add female created characters to their NHL series in NHL 12. After receiving a letter from a fan, who wondered why she couldn’t create herself in the game, EA received permission from the league and…they added few female faces and a wider range of create-a-player sizes when switching gender to “female”. That was it. that was all it took.

And all the sudden the other half of the population can see itself represented in your game, at barely any cost to anybody.

I feel like I should throw out some credit to another sports franchise, an old favorite Baseball Mogul, which for as long as it’s been around has had a feature in which you can determine the year women enter baseball. When setting up a league, you can determine the year in which female rookies can be drafted/show up in minor league systems. Again, this is an incredibly tiny thing, since Baseball Mogul is only a step above an interactive spreadsheet and adding female players only means changing the pool of first names that the spreadsheet pulls from for generating rookies. But the fact that it’s such a small thing is an indictment on other developers who don’t put in the same functionality.

I will concede that sports games have the best excuse of any for the minimal representation of women. There may be licensing issues related to the league, or other similar hurdles to be cleared. I believe that EA had to seek approval of the NHL to add female characters, and there’s no telling what the offices of Bud Selig or Roger Goodell would do with such a request. I would hope they would realize that it was a gesture that didn’t hurt them, didn’t hurt their league, and potentially create a whole new vector for a larger audience. But the world of professional sports can be just as pig-headed and pandering as the world of video games, so who knows.

That doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be a change. And because of games like Baseball Stars and NHL 12, it seems like maybe some of that change can happen in sports games. As far as I’m concerned, it’s not happening fast enough elsewhere. Arguably the two biggest games so far of 2013, Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us were extended escort missions in which the main character was an older, world-weary man protecting a young, naive girl. And they actually represent progress because the female characters in them aren’t helpless and develop as characters. Saints Row IV, the fourth installment of a series in which your character is repeatedly turned into a walking toilet, unfortunately represents a high water mark for equal opportunity representation in big budget, big release games this year. And that’s because it lets your character be anything from a young skinny black man to an old, fat white woman to Nolan North and doesn’t change the story or script one bit based on your choice.

With the exception of MAYBE the cockney guy the female voices in Saints Row 4 are the only way to go. Russian spy, southern belle, or Laura Bailey? What the hell are you doing playing a male character?

Gamer culture needs to change. Any culture that produces examples like these should be taken out behind the woodshed and shot like a rabid dog. Unfortunately, it takes more than one bullet to take down a monstrous, societal behemoth like toxic gaming culture. It needs to be attacked on every end, from every angle, and that includes sports games, as unlikely as they might be.

Baseball Stars had the right idea. Maybe there are reasons that a women couldn’t make it in professional baseball. It may be decades before we know, because a whole lot of old men are going to have to die before it’s even considered. But why can’t a woman make it in video game baseball? Why can’t video games let us play in a better world?